I'm aware that this blog-format is not the most user-friendly. The blogs are now housed and updated weekly over on the 'PDF blog-posts' tab: far easier to read!

|

'Improving core strength' has been the latest trend/buzz-term in fitness and gym circles for what seems like years (so much so that it can't really be termed the 'latest trend' anymore) so you would be forgiven for thinking that a strong core can solve anything! It can't unfortunately, but a strong core is important to maintain posture and balance in everyone, not just those of us with MS (I'll cover posture in a future post). The importance to us though, is that MS can mean that balance can become problematic; research shows that as many as seven out of ten people with MS (PwMS) experience balance problems at some point during the course of the condition, with around one in five people reporting balance problems as one of their first symptoms of MS. It may sound silly, but why is balance important?In pre-MS days whilst studying for my MSc I wrote a piece on osteoporosis and the importance of maintaining bone strength. Much of this research focussed on preventing falls causing breaks at high-risk sites like the hip, wrist and spine and the importance of balance training in helping to prevent potential falls. I carried on to learn much more about functional training for improving balance through my PT qualifications and understood that balance is definitely something we can train for regardless of age or ability. Balance is important primarily to prevent falls, but also (as we all probably already know!) in day to day living; no-one wants to trip down the stairs (or up as I did recently) or to fall over nothing. How can MS be responsible for balance issues?Do you remember the 'tangled wires' analogy from the site? This is where messages sent from the brain to the muscle to perform a specific action get jumbled up and don't necessarily reach the desired destination, get misinterpreted along the way or are too weak to elicit the required action; it maybe that the brain orders the foot to be lifted in order to clear a kerb, but if the message doesn't get through, you'll trip up the step. Many of our MS symptoms can bring about unsteadiness and balance problems, increasing the chance of tripping or falling, including:

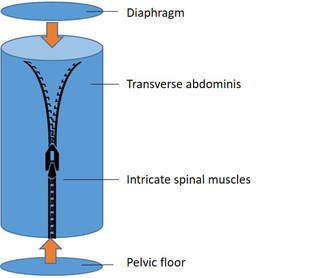

First cautionary note... ...not all balance problems are a result of your MS, if things change or are different to your 'normal' consult your medical team for advice. What is the core and what does it have to do with balance? The core is considered the main trunk of the body once the arms and legs have been removed. A strong core (or core stability) allows us to maintain balance when moving a limb away from the body eg reaching for something on a table or walking; muscles working around the core allow for and correct this imbalance to keep us upright. The core musculature can be visualised as a non-compressible cylinder with the diaphragm at the top, the pelvic floor at the bottom; the transverse abdominis (which compresses the abdominal contents and maintains pressure to protect the spine) wrapped around the sides, all zipped up by the intricate muscles surrounding the spine. Layers of the coreMuscles which support the trunk are arranged in three layers - deep, middle and superficial (outer) - and work together to maintain spinal stability and balance. Often when talking about the core people mistakenly assume we are talking about a visible 'six-pack' or sculpted oblique muscles to pull in and define our tummies. These muscles are an important part of the core but as large (outer) muscles, they are primarily responsible for gross movements such as bending and twisting while other smaller, deeper muscles such as those surrounding the spine play a larger role in subtle movement to maintain balance. The main goal of core stability is keeping the spine supported and protected; without this musculature the spine is inherently unstable putting us at risk of injury. The three layers of muscles surrounding the trunk work together to wrap around the body to allow stability when we move limbs when walking, stretching, leaning etc; any movement which puts the body out of balance. There are many muscles involved in core stability, some major ones include: Deep muscle layer

Middle muscle layer

Outer muscle layer

The core's function is primarily to support and protect the spine while we do activities with the attached limbs eg walking etc in an attempt to throw it off balance! What can I do to strengthen my core?Now we've covered what the core actually is and the importance of using movements which work on all three muscle layers, you can hopefully see that a core training plan isn't just a load of abdominal crunches/sit-ups each day - although, with proper form these can play a role... ...and this is always the challenge of writing about exercise but not providing a training plan for you to follow; it is very difficult to provide personalised training through a blog post or even through an online video (remember my rotator cuff injury of a few years ago?!). Personal Training is by nature 'personalised'; what works for me isn't necessarily suitable for anyone else. I could provide links to a video of core exercises but without knowing you personally I can't find out if they are suitable or whether they will aggravate existing conditions; some core exercises are tricky and need coaching into position, difficult from behind an email. For example, the plank is a traditional core exercise, but unless you have been shown the correct way to perform it, it can give you dreadful back-pain and provide little benefit. What I can do though is add a link to core and balance exercises provided by the MS Trust; these have been shown helpful for many abilities and are promoted within their site. If I can work out how to create the little moving figures perhaps next time I can add some of my own! Exercises for core stability Balance for everyday activities There is a large part of PT-ing which focusses on improving your functional ability in order to perform your daily activities with less energy and effort. Many of our daily activities eg walking, wheeling, carrying groceries, reaching for items on a table or shelf etc will automatically use your core strength already; there is a 'principle of training' around specificity ie train at performing specific tasks in order to be better at them or to make them easier; so rather than setting out to have the 'strongest core ever' why not focus on specifically making daily tasks easier - the more you do something the easier it becomes. Practice intentionally reaching up to pick something off a high shelf, practice balancing to walk along a line at home (a floorboard in the kitchen is my favourite) practice standing on one leg (if you do that a lot!) etc; rehearsing daily activities may provide more benefit than worrying about specific exercises. Final cautionary note Core strength isn't the only thing responsible for improving balance; exercises such as Tai Chi, yoga and pilates are also suggested (which arguably rely on training a degree of core strength too) Please consult a physiotherapist or book a session with a PT to assess which exercises are most suitable and give you a step-by-step guide. As always, safety when exercising is paramount. References:Active IQ (2016) Fitness instructing manual: gym. London: Active IQ

Active IQ (2016) Personal training manual. London: Active IQ Cash M (1999) Pocket atlas of the moving body. London: Ebury press Freeman, J.A Et al., (2010) ‘The effect of core stability training on balance and mobility in ambulant individuals with multiple sclerosis: a multi-centre series of single case-studies’, Multiple Sclerosis 0(00): 1-8. Doi: 10.1177/1352458510378126 Kanis, J. A., McCloskey, E. V., Johansson, H., Cooper, C., Rizzoli, R. and Reginster, J. Y. (2013) 'European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women', Osteoporosis International, 24(1), pp. 23-57. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2074-y. MS Society (2016) Balance and MS (booklet). Available online at: https://www.mssociety.org.uk/ms-resources/balance-and-ms-booklet MS Trust (2016) A-Z of MS: Balance. Available online at: https://www.mstrust.org.uk/a-z/balance Water is essential to maintain life and health. At birth the human body is made up of around 70% water which decreases with age; in the elderly water comprises around 55%. The balance also differs between the sexes with males generally holding more water, and females holding more body fat. Water has functions both within and outside of the body's cells providing a host-environment to maintain vital chemical processes. To remain adequately hydrated - and to prevent dehydration - it is important that water lost through essential bodily processes including breathing, sweating and urination, is replaced. The frequently cited first signs of dehydration are a feeling of thirst and a dry, sticky mouth; but by the time the body had noticed a reduction in water, processed the deficit and sensed the need to respond with a 'feeling of thirst' response the body is already dehydrated. Other symptoms of dehydration include:

Water plays a key role in vital processes within the body, including:

How can dehydration affect my symptoms? One of the first pieces of advice my neurologist gave me was to make sure I made a point of staying hydrated, especially when exercising. When I did some digging around the research on this I realised how valuable it was. Dehydration had been shown to make many of our MS symptoms worse, notably: Fatigue Much of the recent research on fatigue has looked at hydration status; not an unexpected jump given that in people without MS a small drop in hydration can bring on tiredness and confusion. This work is still ongoing but it seems it could be a promising part of the fatigue-puzzle, Urinary tract infections (UTI) We know that some medications used to treat MS can irritate the bladder and cause UTIs; but UTIs and bladder difficulties are a symptom and complication of MS themselves. Some people with MS (PwMS) choose to limit their fluid intake to try to avoid bladder difficulties, but this in itself can lead to development of UTIs and subsequent dehydration. Constipation Adequate fluid intake is important to help to prevent constipation and bowel difficulties; constipation has been shown - in some cases - to affect spasm and spasticity and also aggravate bladder symptoms although specific mechanisms remain unclear. Heat-related exacerbations (Uhthoff's phenomenon) Heat (and in some cases cold) has been shown to being about a temporary worsening of symptoms; adequate hydration can help to maintain a consistent body temperature to help to manage this. How much fluid do I need? The amount of fluid required depends on various external/environmental factors, including:

In the UK, drinks provide around 70-80% of our water needs with the remaining 20-30% coming from foods such as soup, fruits and vegetables, The guideline amount of fluid to consume per day for adults and the elderly is 2,000ml for males and 1,600ml for females. Guidelines for pregnant and lactating women are slightly different (BDA, 2017). If you are interested in the guidelines for children and infants drop me a note and I can send on separately. Water helps to regulate body temperature which can be important when exercising with MS. It is important to increase fluid intake whilst exercising in order to replace fluid lost through increased respiration and sweating. Common household measures include: 1 medium sized glass = c.200ml 1 can of fizzy drink = 330ml 1 mug = c.250ml 1 cup = c.200ml What types of fluid count? Ultimately the type of fluid you consume is up to you, however water (either tap, filtered or bottled) is a healthy option. Tea and coffee count too and can be a useful way of helping elderly family and friends to drink more, but be mindful of the caffeine content. Fizzy drinks contain a lot of sugar as do fruit juices so should be limited. Fizzy drinks can contain a lot of chemicals, sweeteners and sugar which make them a less-healthy option; they also contain caffeine which can prove dehydrating and counteract any benefit of fluid intake. How can I tell if I'm drinking enough? It can be tricky to know how hydrated you are; generally as soon as you feel the first symptoms of dehydration (ie thirst and dry, sticky mouth) you will find a drink which makes you feel better but you will generally stop drinking before you are fully re-hydrated. The colour of your urine is the best indicator; if you are drinking enough your urine should be straw-coloured or pale yellow in appearance. Some lifestyle factors can affect how much fluid you need... Regardless of your fluid intake, some additional lifestyle factors can complicate the body's absorption and use of water and bring about dehydration, Some of these can include:

bladder and affect symptoms which can further impact dehydration. Some practical tips to increase your fluid intake My husband calls me a camel (a bit rude I feel) as I carry water everywhere; in my handbag, in the car, gym bag etc and I drink a lot of water. I suppose I'm lucky as I don't dislike the taste of plain water, but said husband finds it 'boring' and prefers it with some flavour. Some easy/fun ways I've found to make it more interesting include:

References: Active IQ (2016) ‘Hydration’ in Personal Training. London: Active IQ Ltd Active IQ (2016) ‘The importance of adequate hydration’ in Fitness instructing (gym) manual. London: Active IQ Ltd British Dietetic Association (2017) Food fact sheet: fluid. Available online at: https://www.bda.uk.com/foodfacts/fluid.pdf Department of Health (2012) Manual of nutrition, Twelfth Edition. London: The Stationary Office MS Trust (2016) A-Z of MS: diet. Available online at: https://www.mstrust.org.uk/a-z/diet On the first day of my PT training course I sat at the front (always the swot!) next to a friendly lady who turned out to be a competitive gymnast, introducing herself as 'hypermobile'; 'OK' I thought, 'she means a bit bendy'... Once we got into the gym she was certainly bendy, turning perfect cartwheels and back-flips whilst we waited for the instruction to begin. She explained that as a gymnast her main focus was on keeping her joints supple and able to move as far as possible to complete strings of specific movements; she told us that she carries out a short stretching routine each morning to allow the joints to move freely in order to make the most of her days' training and help to prevent injuries. Why is flexibility important in MS? Clearly we're not all gymnasts aiming to effortlessly do the splits (or perhaps you are? Jolly well done if so; I was part of a gymnastics club when I was little and never managed to do the splits). Splits aside, maintaining flexibility is important in MS to help reduce the day-to-day demands placed on the body through daily activities (themselves often made more difficult whilst dealing with MS), and also to help manage symptoms like muscle stiffness, spasticity and muscle tightness and help improve posture and balance. What do we mean by flexibility? As we went on to understand, flexibility doesn't only mean cartwheel-spinning and back-flipping gymnasts it refers to the range of movement possible around each joint or series of joints. The level of movement ('range of motion' or ROM) is determined by the shape of surrounding bones and cartilage, the length of the muscles around the joint and the ligaments and tendons crossing over the joint to allow movement. How/why is flexibility relevant to MS? The nervous system plays an important role in flexibility; it is responsible for determining muscle tone (tension) which allows movement. Some of the diagnostic tests that neurologists perform look for the level of muscle tone ie level of tension or resistance specific muscles can provide when force is applied. Muscle tone is the tension which allows us to move limbs and hold a limb in position. An increase in muscle tone is responsible for symptoms of spasm and spasticity.

How can stretching help to improve flexibility?

Methods of stretching 1. Maintenance stretching Involves short stretches in muscles which aren't particularly tight; often carried out during warm-up and cool-down phases of activity. Muscle taken to the point of mild tension and held for 10-15 seconds to maintain flexibility. 2. Developmental stretching Used to increase flexibility; the muscle is stretched in the normal range of motion then when it relaxes in position it is taken a little further and held near the end of the range of motion for 30-60 seconds to increase flexibility. This is not recommended during the warm-up phase as the muscle needs to be warm. Types of stretching A muscle is lengthening and stretching when it's opposite ends move further apart and away from each other (no anatomy lesson this week (!) but they're technically called the 'origin' and 'insertion' of the muscle). There are a few ways to achieve this lengthening: 1. Static stretching Static stretching involves stretching a muscle and holding in a challenging but comfortable position for a period of time. 2. Dynamic stretching Dynamic stretching involves moving a limb into position near the end of the range of motion, under control. Often used during a warm-up phase to keep heart-rate elevated. Repeated 8-10 times to improve flexibility and increase ROM Long-term benefits of improving flexibility General benefits of working to improve your flexibility - outside of specific benefits to our MS include:

A word of caution... This wouldn't be a post from me without a few words of caution; 1. Always make sure your muscles are warmed up before stretching: stretching cold muscles can result in injury. 2. Only stretch your muscles to a point of mild tension. 3. Be careful not to jerk or force you muscles into a stretch position which can cause jarring and injury 4. Be careful not to over-stretch a muscle: working at the furthest end of a muscle's range of movement can cause injury. 5. Stop if you feel pain; I know I've said it before, but 'no pain, no gain' doesn't apply when exercising with MS. 6. Please consult a PT for clarification and example exercises if symptoms of spasticity and spasm are a challenge for you. OK, sorry, six words of caution but it's important to stay safe when doing any form of exercise. References: Active IQ (2016) ‘Principles of exercise, fitness and health; flexibility’. In: Fitness Instructor Manual. Active IQ Ltd, London Gibson, B. (2016) Stretching for people with MS: an illustrated manual. National Multiple Sclerosis Society; NY: available online at: https://www.nationalmssociety.org/NationalMSSociety/media/MSNationalFiles/Brochures/Brochure-Stretching-for-People-with-Ms-An-Illustrated-Manual.pdf MS Society (2017) Muscle spasms or stiffness. Available online at: https://www.mssociety.org.uk/exercise MS Trust (2015) Spasticity and spasms. A-Z of MS. Available online at:https://www.mstrust.org.uk/a-z/spasticity-and-spasms Many people with MS (PwMS) can find it difficult to achieve and maintain a healthy weight, experiencing unexplained weight gain or weight loss. This isn't helped by the nature of the disease making it difficult to rely on the tried-and-tested weight management techniques that you may have used in the past, pre-diagnosis. Whilst weight management can be a challenge for everyone - not just those of us with MS - but adding some of our 'unique' challenges into the mix can make it seem double difficult to manage and all the more frustrating. Why is it important to maintain a healthy weight?Achieving and maintaining a healthy weight is primarily important in aiming to reduce the risk of diseases including:

Poor nutrition and associated impact on weight can exacerbate conditions including:

and increase the risk of cardiac events including:

Why can we struggle to maintain a healthy weight with MS? On a basic level maintaining a consistently healthy weight generally means that we are consuming enough energy to support our essential bodily processes. There is a distinction here between 'energy' and 'nutrition'; being a healthy weight does not necessarily mean that we are consuming an adequate level and balance of essential nutrients, just that we are eating enough volume (ie energy) to function. But what happens if we aren't? Weight-related challenges we can face with MS 1. Weight gain in MS Weight gain in MS is common with the MS Trust reporting that over 50% of sufferers are overweight. This is unsurprising given the nature of the disease and its effect on symptoms including pain, energy levels, fatigue and balance affecting the ability to exercise; comfort while moving around and general mobility challenges meaning that exercise isn't possible nor comfortable. Symptoms of depression and anxiety can mean that you might not feel confident enough to exercise and you might feel better staying in the house...which can lead to comfort eating in a bid to make yourself feel better. All these points can mean that regardless of exercise you may not be 'out and about' as much as you were. If you have greater mobility challenges and spend part of your day in a wheelchair you may feel you are facing a greater challenge to maintain a healthy weight; remember that weight-loss isn't all down to exercise (although this is an important element) there is much you can do to reduce your weight through balancing your intake according to activity levels; choosing high-fibre foods which will fill you up and making healthy choices (eg apple or few nuts) when snacking. Following on from last week's blog too there are many ways you can exercise whilst in a wheelchair. Treatment choice may play a role here too; although rarely listed in manufacturer literature there are many threads on forums such as Shift.ms for example where members post queries around weight gain through taking a particular Disease Modifying Therapy (DMT). Weight-gain is an unfortunate 'known effect' however in taking prescribed steroid treatments to reduce inflammation during a relapse. What can I do about it?Unfortunately this isn't the correct forum for me to give out specific weight-loss plans - that is the role of a dietitian and needs specific one-to-one advice or as part of a weight-management group - I'm sorry if that was what you were expecting from this blog. If you are concerned about your weight; as ever please consult your MS nurse or GP, they will be able to give you some advice and sign-post you to a relevant group or refer you to a dietitian; weight loss if far more than just monitoring what you eat and involves bench-marking where you are; working out what you want to achieve (making sure that it is realistic and achievable) and helping you to set realistic short and longer term goals. In a nutshell - much more than can be done in a single, public blog post. The first cautionary note As ever, there is a cautionary word that goes with this... In the same vein as my (often laboured) advice about not following 'YouTube celeb's' workout videos (remember my expensive Physio costs that I mentioned last week as a result of pre-PT qualification video-following?) the same is true - if not more so - of following celebrity diet advice, that often promise you a dramatic weight loss in a short amount of time. Diet advice is big-business at the moment with everyone from PTs (who incidentally aren't qualified to prescribe anything more than generic dietary advice) to models trying to cash in on the public desperation to lose weight. You may have seen the hashtag on social media and I definitely use it: #trustadietitian. Always consult an expert. 2. Weight loss in MS Weight loss can also happen in MS with symptoms such as tremor, problems with posture or problems with swallowing (dysphagia) making the physical act of eating difficult. Fatigue relating to selecting, shopping for and preparing food, symptoms of anxiety, depression and challenges with cognitive functioning can all make eating difficult or cause you to lose your appetite. Similarly some DMTs can have the same effect, all making you likely to lose weight. . Why is weight loss a problem? Given our culture of 'celebrity' and focus on slim physique (although it seems to be shifting towards a more 'fitness-based' culture) you could be forgiven for wondering that the bother with weight loss is... Malnutrition. If you are unable to consume an adequate intake of energy (and essential nutrients) to maintain normal functioning of your bodies' systems you will become malnourished. This is a problem in terms of symptoms including fatigue and depression, but can have wider challenges such as health of the digestive system; reduced immunity to other conditions; reduced mental functioning and can lead to muscle wastage (remember the resistance-training blog where I said we must 'use it or lose it' in relation to maintaining muscle strength?). It can be difficult to notice the symptoms of malnutrition as early signs include muscle-weakness and fatigue - both symptoms of MS in themselves so may go unnoticed. What can I do about it? If you are struggling with eating or preparing meals please speak to your GP or MS nurse who can refer you to a dietitian; weight-gain is not as simple as just 'eating more' and the problems behind why you may have lost weight such as those mentioned above, can be treated successfully by your medical team. If you are struggling with loss of appetite it may be suggested that you exercise to stimulate your appetite; this will need to be referred specifically to a PT to provide you with a plan to make sure you don't lose weight. The PT will focus on building up your lean muscle which will help to stimulate your appetite. A second cautionary word... It is important to remember that rapid weight loss may be a symptom of other conditions; if rapid, unexplained weight loss is the case for you please visit your GP for advice. How can maintaining a healthy weight help me to manage my MS? Aside from the illnesses mentioned above (which are pretty serious) there are also specific ways in which keeping a healthy weight can directly impact our ways of managing our MS. Having a healthy weight can:

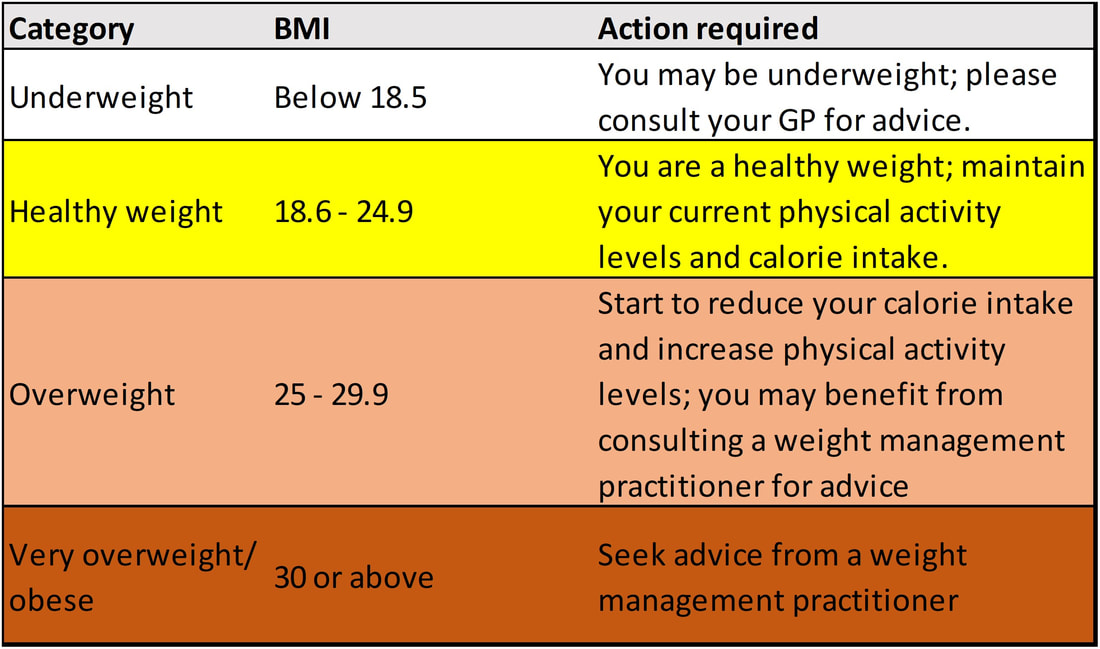

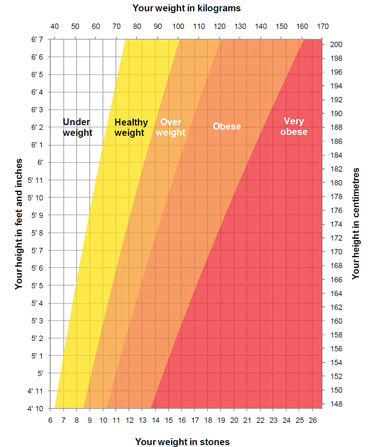

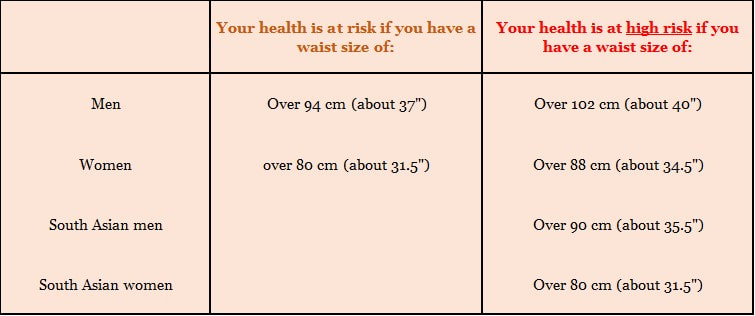

What do we mean by a healthy weight? There are two easy tools we can use to help identify this: one useful method is to calculate your Body mass Index (BMI) which gives a number based on how your bodyweight relates to your height (although comes with some limitations) and another calculation based on your waist circumference (WC). Although these tools are useful in providing a guide it is important to consult your GP or MS nurse if you are concerned about your weight; there are various caveats (detailed below) which mean that these tools are not suitable for everyone. 1. Body Mass Index (BMI) BMI can be assessed using this chart and is calculated by: 1) Measuring your height in metres and weight in kilograms (both without shoes) 2) Multiply the figure for height by itself 3) Divide your weight in kilograms by the answer noted in the previous step. Or use this chart for a quick reading... (Chart references below) Limitations of the BMI model Classifying weight into a category according to BMI is a useful guide, however does have limitations:

2. Waist circumference (WC) Your shape - indicative of where you carry excess weight - can also indicate your health risk. Carrying excess weight around the middle can increase the risk of developing coronary heart disease, high blood pressure and diabetes. You can easily assess whether your shape is putting you at increased risk by measuring the circumference of your waist by following the handy tips from the British Heart Foundation below. At present guidelines exist for people of European and Asian ethnicities while data for other ethnic groups is not available; if you are not of Asian background current recommendations indicate that you should follow guidelines for European men and women. Separate guidelines exist as data shows that individuals of Asian ethnicity are more likely to have a higher proportion of body fat to muscle compared to the rest of the population. People of Asian background tend to carry this fat around their middle meaning that they are at greater risk of developing problems including diabetes and coronary heart disease at a lower waist size than Europeans. However, no matter what your ethnic background it is important to remember that the measurements below are a guide. If you are unsure please consult your doctor who will be able to make an individual assessment of your overall health risk based on your individual risk factors. British Heart Foundation (BHF) guidelines for waist measurement (Bear with me, I'm not teaching you to suck eggs here; there are some useful notes...) 1. Find the point halfway between the bottom of your ribs and top of your hips; this will probably be in line with your tummy button or slightly higher. Measure yourself around the middle point. Remember to start at the lowest end of the tape measure and try to relax and not breathe in! 2. Check your measurement on the chart below; it is recommended that men use the metric measures (cm) while women use imperial measures (inches). Source: Source: British Heart Foundation (2011). 'Session 13 sheet: Waist measurement instructions' (available online at www.bhf.org.uk) And finally...! To reiterate for a final time (this blog is getting a bit long, apologies) please consult your GP or MS nurse if you have concerns about your weight; as I said earlier - it's not as simple as just eating a bit more or less, there could be other underlying conditions responsible for weight loss/gain. As always, the last word from me...Do let me know if you have found this post helpful; use the icons below to send me an email; join me on Twitter or send me a message through the contact page on the website, I'd love to know what you think. References:

Active IQ (2016) ‘Section 7: the importance of healthy eating’ in Fitness instructing (gym). Active IQ Ltd: London British Heart Foundation (2011) ‘Session 13 sheet: waist measurement instructions’. Available online at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/heart-health/preventing-heart-disease/managing-your-weight British Nutrition Foundation (2016) ‘Healthy weight loss’: Available online at: https://www.nutrition.org.uk/healthyliving/healthissue/healthy-weight-loss.html MS Society (2017) ‘Managing your weight’. Available online at: https://www.mssociety.org.uk/managing-your-weight MS Trust (2016) A_Z of MS; ‘Managing weight’. Available online at: https://www.mstrust.org.uk/a-z/diet#weight NHS Choices (2015) ‘height/weight chart’. Available online at: http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/loseweight/Pages/height-weight-chart.aspx Waters, P., (2014) ‘The complete guide to weight-loss’. Bloomsbury: London World Health Organisation (2017) Body Mass Index (BMI). Available online at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi Pictures by Pixabay unless noted specifically. What do we mean by cardiovascular fitness? Cardiovascular (CV) fitness is the ability of our heart, lungs and muscles to take in, transport and utilise oxygen during exercise or any daily activities which make you breathe a little harder and pump your blood a little faster (you may have heard it referred to as cardio-respiratory fitness, stamina and aerobic fitness too). CV activities do not refer exclusively to traditional, structured 'exercise'; any activity where your heart rate is raised for a prolonged period and you start to feel out of breath counts too. My friends and I giggled during the personal training course when 'gardening' was used as an example of an activity which raises heart-rate and gives you a good workout; I live in the centre of a town where my gardening is limited to a couple of hanging baskets and a stone courtyard, but on mentioning this to my parents who live in the countryside they agreed wholeheartedly that it definitely provides them with a good form of exercise! CV activities increase the heart rate and breathing rate with the aim of increasing blood flow and delivering more oxygen to the body to produce energy. When the pulse quickens and breathing gets deeper the cardiovascular system is working. Activities that will improve the efficiency of the heart, lungs and circulatory system- thereby improving CV fitness are those which use the large muscles within the body in a continuous and rhythmic way and include activities such as walking, running, swimming, cycling, rowing, dancing and aerobics classes. Long-term benefits of cardiovascular exercise (for the general population and us) CV activities have a number of benefits to the body:

How can cardiovascular activity help to manage some of my MS symptoms? Alongside the general population health benefits of CV activity (available to all regardless of MS status), research has shown specific benefits to people with MS (PwMS) in terms of symptom management and improved ability to complete daily activities (known as ADLs: Activities for Daily Living). Regular CV activity has been shown to improve:

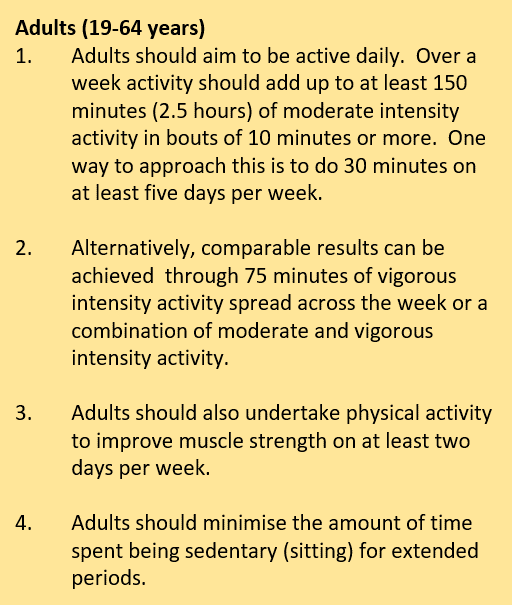

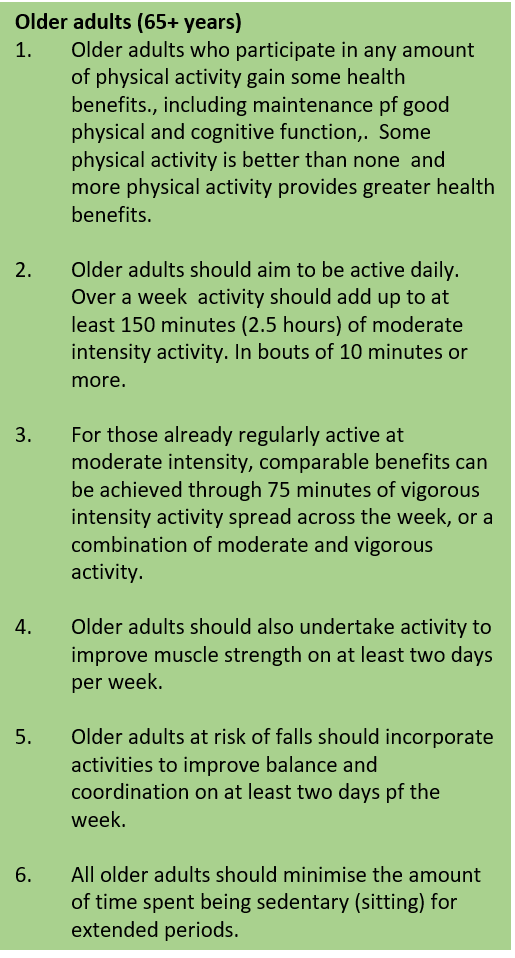

How much cardiovascular activity should I do to reap the benefits? The guidelines below were published for the general population (ie those without MS) by the UK Department for Health in 2011 but it has become accepted that as far as is reasonable these apply to PwMS too (full reference below). It is understood that the nature of the disease and the varied symptom patterns may make any level of activity challenging, however the benefits of CV activities to health outside of our MS are huge (as detailed earlier in this blog). As I mentioned in the previous resistance-training blog (and labour a little on the site!) the popular adage 'no pain, no gain' simply doesn't apply when exercising with MS; you should only do what is realistic for you and only you know that: not a personal trainer, training buddy or the distance of a run or bike ride you signed up to... just YOU. Ways to incorporate CV activity into your day We are all so busy; life is so busy so it can be difficult to find time to exercise or spend time on activities. It is often easiest to 'find time' if you can incorporate moving a bit more into your daily life (as much as you are able) so it doesn't feel like a 'special effort' or that it is taking time away from something else. I'm a big fan of choosing activities that family members can join in with too: two birds with one stone as it were - quality time and exercising: win-win. Some ideas from me:

A few thoughts from the MS Trust on exercising whilst in a wheelchair If you are a gym-goer there are lots of adaptations available for using machines like the rowing machine or arm-cycling machines - both are great CV activities. At home - a suggestion from the MS Trust's neuro-physiotherapist Liz Betts is arm-jogging whilst watching the TV or working on balance whilst waiting for the kettle to boil. Small consistent actions can really make a difference to your fitness. A few extra bits on exercise and MS I'm conscious that when most people (me included) talk about 'exercise' in general-chat we often mean CV activities like running or cycling. Whilst I do use weights frequently - more than the twice-per-week recommended - I don't automatically jump to think of deadlifts if exercise is mentioned. On that basis there are a few extra points about exercise there are pages dedicated to them on the site but I think they're relevant here. Heat and CV exercise You may remember from the recent blog on heat and MS symptoms (Uhthoff's Phenomenon: available here if you missed it) that CV exercise is more likely to raise body temperature than resistance training because CV activity increases blood flow and therefore generates heat (that's the point of CV activity!). Nonetheless heat can be a problem; do check out the previous blog mentioned above to see tips for managing this if it is a problem for you. Can I exercise during a relapse? Advice from the MS Society shows that exercise during a relapse does not make MS worse in the long term and that exercise does not trigger relapse. Advice is not to exercise until symptoms have levelled off and any steroids - prescribed to help you through the symptoms - have finished. A physiotherapist can help you get back into an exercise routine once the relapse is finished and can provide advice on strengthening activities for any affected body parts. A physiotherapist is more suitable than a PT to 'prescribe' movements for rehabilitation. If in doubt, please consult an expert... Please don't be afraid to ask for help if you're trying to work out how to start exercising; part of the PT course discusses MS so a qualified personal trainer can help put together a plan for you - in or out of the gym. It is important that you explain about your MS and don't be embarrassed about admitting there are things you find difficult, the emphasis here is on 'personal' training so they can put together a bespoke plan which works for you and keeps you safe: safety whilst exercising is paramount. For specific mobility-related queries it may be best to consult a physiotherapist too. On that note, be careful about following YouTube videos by fitness bloggers; they are qualified in their own areas but they don't know you personally: one size does not fit all in terms of exercising with a condition like MS. From personal experience pre-diagnosis and pre- PT qualification it can be costly in terms of physio appointments to repair any damage caused by following videos with no-one to correct possible poor form. This is part of why I keep focussing on safety with anything to do with exercise. If you haven't exercised for some time be sure to get agreement from your GP before you start to make sure there are no other factors you need to consider first. References:

Active IQ (2016) Fitness Instructors Handbook. Active IQ: London Betts, L (2017) ‘Practical tips staying active’. Open Door (May); London pp.16-17 Coulson, M. (2011) ‘Multiple sclerosis’ in The complete guide to teaching exercise to special populations. Bloomsbury: London pp.133-140 GOV.UK (2011) 'Start active, stay active'. A report on physical activity from the four Home Counties' Chief Medical Officers. Available online at: www.sportengland.org/media/2928/dh_128210.pdf Langeskov-Christensen, M. et al., (2015) ‘Aerobic capacity in persons with MS: a systematic review and meta-analysis’. Sports Medicine, 45(6):pp. 905-923 Latimer-Cheung, A.E. et al., (2013) ‘Effects of exercise training on fitness, mobility, fatigue, and health-related quality of Life among adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review to inform guideline development’. Arch Phys Med and Rehab 94(9): pp.1800-1828 MS Society (2017) Exercise. Available at: https://www.mssociety.org.uk/exercise MS Trust (2014) A-Z of MS: Exercise. Available at: https://www.mstrust.org.uk/a-z/exercise What's all this fuss about our gut at the moment? The suggestion that the bacteria naturally living (happily and relatively quietly) in out gut could contribute to our overall health and disease status began to emerge as a concept in around 2010. It has begun to gather serious momentum over the last few years on social media with 'Insta-celebs' posting about the benefits of eating fermented foods to 'rectify' or 'calm' gut bacteria. It is often discussed in relation to bowel conditions and food intolerances but for us there is a more interesting suggestion on how our gut bacteria may be heavily implicated in the development of autoimmune diseases. A quick word on terminology This relatively recent upsurge in interest around the gut has inevitably piqued interest in the popular press and has muddied the water somewhat in terms of what exactly is being talked about. I have seen the terms 'microbiota' and 'microbiome' used seemingly interchangeably in some popular press so in the interest of clarity:

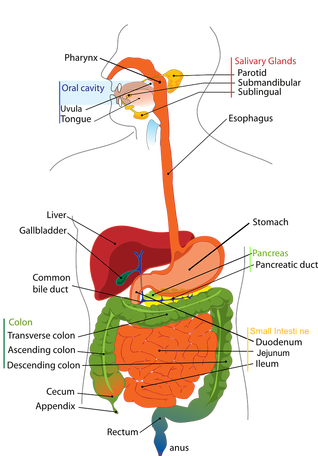

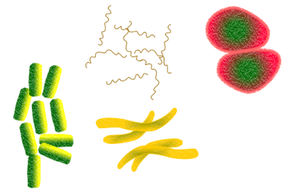

Where is our gut and what does it do? Our gut - the long tube also called the digestive tract - runs from the mouth, down the gullet (oesophagus), through the stomach, small intestine, large intestine and anus, The gut is concerned with breaking down, processing, digesting and absorbing nutrients from food. Various organs are involved within this process from chewing and the action of digestive enzymes in the mouth; chemical breakdown and some absorption from the stomach; movement to the small and large intestine for further absorption and finally anything not absorbed by the body is expelled at the end of the tract (anus). This is not meant as a biology lesson but illustrates how large the gut area is and how important it is in its functioning. The gut microbiota The human gut plays host to trillions of bacteria and viruses which have tremendous potential to impact various facets of our health; they contribute metabolic functions, protect against pathogens and educate the immune system. The composition of bacteria in our gut begins in utero and continues for the first 2-3 years of life. Recent studies have shown both short and longer-term effects on the composition of the microbiota in relation to:

The intricate composition of the gut has been described as our 'secondary genome' and is as individual as our genetic make-up. It lies in close association with with the host's (our) immune system and together plays a role in exerting various nutritional, metabolic and immunomodulatory functions important to our overall health and wellbeing. Links between gut microbiota and disease Research into the gut microbiota to date has shown this bacteria implicated in the development of diseases including:

What do we currently understand about the possible implication of the gut in the mechanisms of these diseases? The combination of different types of bacteria was shown to be imbalanced in individuals with these diseases. Some studies have shown this imbalance to be considerable in patients with MS with considerable under-representation of some bacteria and over-representation of others. The microbiota can be deeply influenced by external factors as mentioned earlier in this article, and its aim is to maintain equilibrium between the host (us) and the environment thus keeping an optimal balance of different bacteria. Given the location and function of the gut diet has become the focus of much exploration. Dietary intake has been shown to be a key determinant in microbiome composition and diversity; this may have clinical implications here as evidence suggests composition of the microbiota in early life may be responsible for the programming of gastrointestinal , immune and neural development: key features in the diseases mentioned above. How could this be relevant to my MS? This may be pertinent here as when balance is maintained between the microbiome and metabolism of the host, all is well; when imbalance occurs inflammation and infection can result. As we know, in MS it is inflammation that is responsible for damage to the central nervous system; the symptoms we may present and the resulting build-up of disability. I would love to tie this post up with a great dramatic conclusion (which might have been what you were waiting for - apologies), however this research in humans is at a relatively early stage so the conclusions aren't there yet. The hope is that in the future it can be used to develop further theraputic interventions and understand more about the fundamental mechanisms of disease development and progression. A cautionary word (disclaimer) This post began as an expected exploration of how diet can influence the gut (I'm aiming to alternate between diet and exercise each week in the blog posts). However this has turned into something much bigger that I have been interested in but haven't explored until now. I have no history within this area and I'm a little concerned that it is venturing out of what I set this blog up to share: ie things I know a lot about. So to be very transparent, this is a brief overview of some of the latest research papers; it is not a comprehensive literature review of all the research and conclusions produced to date. All the papers I have used to write this are referenced below so if you are hoping to use this for anything other than your own interest please consult one of the researchers working in the area; as always, consult an expert - this time, it's not me. References:

Adamczyk-Sowa,M. et al., (2017) ‘Does the gut microbiota influence immunity and inflammation in multiple sclerosis?’, Journal of Immunology Research, [epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1155/2017/7904821 Donovan, S.M. (2017) ‘Introduction to the special focus issue on the impact of diet on gut microbiota composition and function and future opportunities for nutritional modulation of the gut microbiome to improve human health’, Gut Microbes 8(2): 75-81 Glenn, J.D. and Mowry E.M., (2016) ‘Emerging concepts in the gut microbiome and multiple sclerosis’ Journal of Interferon and Cytokine Research 35(6): 347-357 Jangi, S. et al., (2016) ‘Alterations of the human gut microbiome in multiple sclerosis’, Nat Commun28(7): 1-11 Newland, P.K., Heitkemper, M. and Zhou, Y. (2016) ‘The emerging role of the gut microbiome in adult patients with multiple sclerosis’, J Neurosci Nurs 48(6): 358-364 Shailesh, S.K., Freedman, S.N and Mangalam, A.K. (2017) ‘Gut microbiome in multiple sclerosis: the players involved and the roles they play’, Gut Microbes July 11: 1-9 [epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1349041 Have you found that some of your MS symptoms can feel like they get worse in the heat? We're told - and might even be expecting - this to happen if we go away to a hot country on holiday (to sunbathe!), it's natural that heat an make everyone feel more tired but for many people with MS (PwMS) any activity which raises the core body temperature can bring on a temporary worsening of symptoms. This has been shown to happen when cooking, sunbathing, taking a hot bath or shower and while taking part in aerobic exercise eg running, cycling etc. What happens? Research shows that heat sensitivity is common in MS with between 60 and 80% of PwMS reporting worsening of symptoms including a build up of fatigue, blurred vision, loss of balance or increase in cognitive symptoms such as concentration and memory when exposed to heat. The effect on balance, motor skills and vision can become more evident when exercising as aerobic exercise raises heart rate rapidly which in turn increases body temperature as blood is being pumped more quickly around the body and we eventually begin to sweat in an attempt to cool down.. This can happen almost immediately or over a more prolonged exercise period; much of the research on time associated with symptom exacerbation is dependent on intensity of exercise in relation to rapid increases in temperature. Although symptoms can be unpleasant the effects are temporary and are generally quickly reversed once body temperature returns to normal; the effects of heat do not cause permanent damage to nerves. From a personal perspective this decrease in function was the symptom which led to my diagnosis; it's hard to call yourself a 'fast-runner' if your leg decides not to work properly after 15 minutes or so! Why does this happen? There is some evidence which shows that PwMS can't regulate body temperature as effectively as those without MS which may mean that core body temperature increases more quickly triggering this heat sensitivity. Changes in temperature affect the way our nerves function and make it more difficult for them to send and receive messages. The fatty myelin coating surrounding nerves encourages effective transmission of nerve impulses (messages) from parts of the body to the CNS; as you know, in MS the myelin costing is damaged meaning that the nerves are more exposed and less protected making it more difficult to transmit accurate messages. Myelin is also responsible for protecting the nerves from changes in temperature so where our myelin had been damaged we are less able to manage changes in temperature. This process is not fully understood but recent research has shown that increases of only 0.5 degree Celsius can bring about an increase in symptoms. It is also possible that MS lesions can occur in areas of the brain responsible for temperature control and regulation thus making it more difficult to keep cool. Why 'Uhthoff's Phenomenon'? Ever the (inquisitive, nosy) scientist, I was curious about this term as soon as it was mentioned to me and was indeed the first indication that anything was wrong; so I set about 'doing some research'... Early on, it was mentioned to me when explaining the condition, that as recently as 1983 one of the tests for MS was to immerse a patent into a hot bath for 10-15 minutes and see what happened! In 1890 Professor Uhthoff noticed the transient worsening of MS symptoms once patents were immersed in the hot water. The key symptom assessed initially was visual and how the optic nerve was affected by increases in heat (optic neuritis). This finding lead to the early advice to PwMS not to undertake exercise for fear of worsening symptoms. This lead to conservative advice in regard to rehabilitative exercises and resulted in subsequent deconditioning of patients through lack of exercise (do you remember last week's blog on resistance exercise in maintaining muscle strength?. A real example of 'use it or lose it'). It wasn't until 1961 that this finding was given his name and what we commonly refer to now as 'Uhthoff's Phenomenon'. What can we do to manage heat sensitivity whilst exercising? The research provides some practical tips to manage the heat:

A word for the girls... Whilst this blog focusses on the effects of heat in relation to exercise, women are naturally more susceptible to changes in body temperature than men as a result of hormone-induced processes including menstruation and pregnancy; both of which naturally increase your core body temperature. What about cold? Although worsening of symptoms has most commonly been reported in the heat, some people find that decreases in temperature have a similar effect. As is widely reported 'no two people experience their MS in the same way'. Temperature sensitivity is an irritating symptom which can be difficult to get away from if you are badly affected. I've provided a few tips above and there are more on the website. Exercise is an important part of helping to manage this disease so as far as you are able, it is worth trying to find a solution which works for you. As always, the last word from me... Do let me know if you have found this post helpful. Send me an email: hello@healthylifems.com; send me a tweet [@healthylifems] (or use icons below) or send me a message through the contact page on the website, I'd love to know what you think. Diana xx References:

Active IQ (2016) Personal Training Manual. Active IQ, London. Davis S.L., et al (2010) ‘Thermoregulation in multiple sclerosis’ Journal of Applied Physiology. Nov 109:5: 1531-1537 Filingeri, D. et al., (2017) ‘Afferent thermosensory function in relapsing – remitting multiple sclerosis following exercise-induced increases in body temperature’ Experimental Physiology, Aug 1; 102(8): 887-893 MS Trust (2015) ‘Heat sensitivity’. Available at: https://www.mstrust.org.uk/a-z/heat-sensitivity MS Society (2017) ‘Handling the heat’. Available at: https://www.mssociety.org.uk/ms-research/research-blog/2017/06/handling-heat-latest-research Opera, J.A. et al. (2016) ‘Uhthoff’s phenomenon 125 years later – what do we know today?’ Journal of Medicine and Life, 9(1): 101-105 The idea that antioxidants could be helpful in limiting the damage that MS causes in the central nervous system (CNS) has been suggested by some researchers exploring the action of oxidants (or free radicals) on disease.This suggestion may seem a little far-fetched on the surface until we consider that antioxidants have been shown to help protect the body against heart disease and some cancers; so it's a relatively short jump - once we understand how oxidants can damage the body - to the idea that they could be helpful in limiting damage in MS. What are oxidants and what is their relevance in MS? Oxidants are highly reactive chemicals which bind to - and change - the structure (and therefore function) of specific structural components of the body. Essential fatty acids (EFAs) are of particular interest for us with MS as they form much of the structure of cell membranes, myelin and DNA, and are highly vulnerable to damage from oxidants through an oxidation process. Oxidants have therefore been suggested to attack the EFAs within the CNS which may be responsible in part for the damage caused in MS. Oxidants are found in many every-day items including alcohol, tobacco smoke, fried foods, pesticides and air pollution; by their very nature it is difficult (even impossible) to avoid them so some research has focussed now on how we can protect ourselves and theoretically limit the damage caused by oxidants. The role of dietary antioxidants in protecting against oxidative damage Research has focussed on the protective nature of antioxidant vitamins to guard against oxidative damage to the body; if you're interested, this oxidation is the same process responsible for structural degereration of the body as we age, so antioxidant vitamins have many other, more aesthetic, uses within the body too! The antioxidant vitamins are vitamins A,C and E. The antioxidant vitamins 1. Fat-soluble vitamins Vitamins A and E are fat-soluble vitamins so can be stored in the body for some time and do not need to consumed daily. Vitamin A Vitamin A is responsible for:

Vitamin E Vitamin E is responsible for:

2. Water-soluble vitamins Water-soluble vitamin cannot be stored in the body in any great quantity so much be consumed as part of the diet on a daily basis. Vitamin C Vitamin C is responsible for:

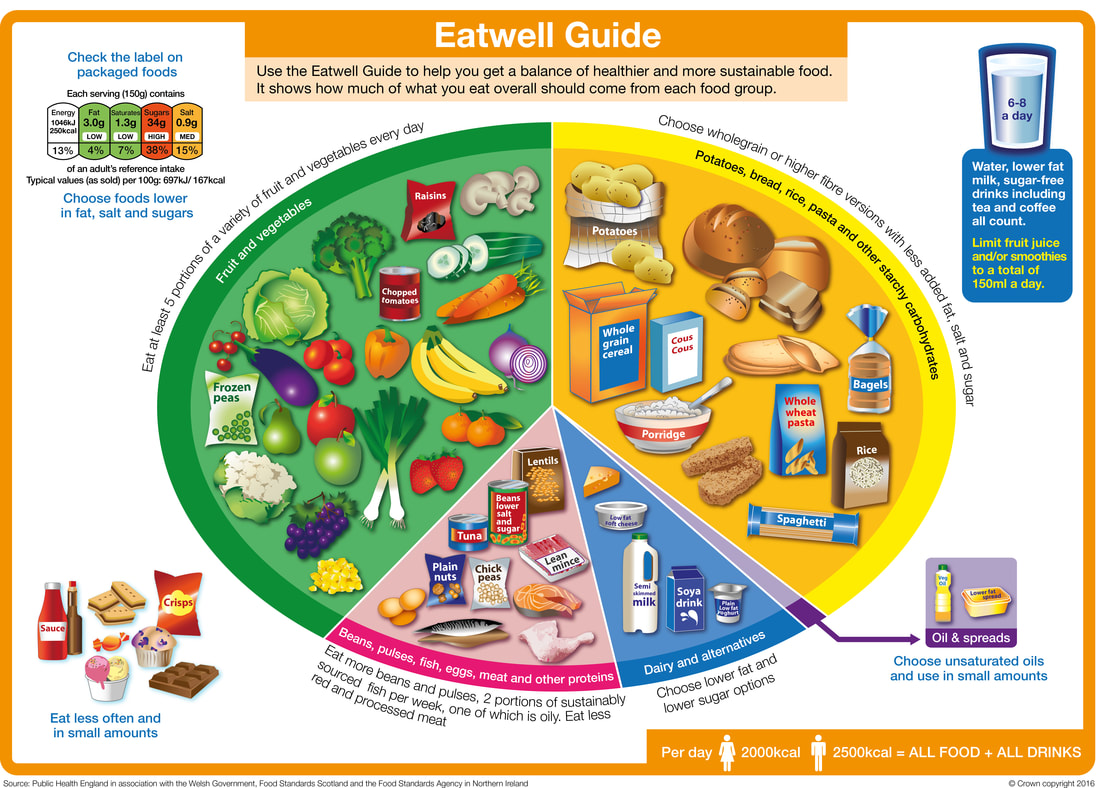

Individual vitamins and minerals are great, but... The importance of a whole-diet approach A word of caution; individual vitamins and minerals are a very important part of a healthy diet however it's important to remember that we eat a varied diet made up of multiple combinations of different foods; so whilst these vitamins are key to the various important processes be mindful of not excluding other important vitamins and nutrients too. A cautionary word about antioxidants Despite the seemingly common-sense theories of antioxidant use in MS (as explained above) there is not enough conclusive evidence published as yet to recommend their use as a preventive treatment for MS. Much in the same way as with 'special diets' promoted to help in MS as detailed on the website ( http://www.healthylifems.com/the-diet-debate-in-ms.html ) this same advice holds true; there is likely no consensus published because there is not enough evidence available. This is an area still being researched so it will be interesting to see what (if any) further advice emerges in the next few years. A less-cautionary word about antioxidants! One thing that we do know about general health, regardless of their role in MS, is that antioxidants are important in the specific functioning of the body and the prevention of certain other diseases mentioned above: some cancers and coronary heart disease. The advice about the consumption of foods rich in dietary antioxidants underpins the UK Department of Health's '5-a day' message to consume at least five portions of fruit and vegetables per day for general health and wellbeing, so regardless of whether research in the future does show antioxidants to be beneficial as a treatment (or partial treatment) for MS it is important that we all, regardless of our MS, consume a varied diet with a selection of different fruits and vegetables each day. A helpful piece of advice given by many dietitians is to make sure that we 'eat the rainbow' ie eat a variety of multi-coloured fruits and vegetables each day to maximise vitamin and mineral intake. This image taken from the British Heart Foundation illustrates this advice nicely although they are quick to point out that overall daily intake of fruit and vegetables is more important than focussing on the range of colours, but I think it is a helpful reminder when preparing meals to think to yourself 'if there is enough colour on my plate'? Final words from me Have a look at my website to understand more about how diet can help us manage some of our specific MS symptoms. Do let me know if you have enjoyed this post and found it useful. Send me an email (address below); send me a tweet (@healthylifems) or send me a message through the contact page on the website, I'd love to know what you think. Diana xx References:

Active IQ (2016) ‘Applying the principles of nutrition to a physical activity programme: antioxidants’ in Personal Training Manual. Department of Health (2012) Manual of Nutrition. 12th ed. The Stationary Office; London Department of Health (2017) The Eatwell Guide. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-eatwell-guide Farinotti M, Vacchi L, Simi S, Di Pietrantonj C, Brait L, Filippini G. (2012) ‘Dietary interventions for multiple sclerosis’. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Issue 12. Art. No.: CD004192. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004192.pub3 Garrow, J.S., James, W.P.T. and Ralph, A. (2000) Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 10th ed. Churchill Livingston; London Gibney, M. J., Margetts, B.M, Kearney, J. M and Arab, L. (2012) Public Health Nutrition. Blackwell Science; edited on behalf of The Nutrition Society: London MS Society (2016) Diet and Nutrition booklet: available at https://www.mssociety.org.uk/ms-resources/diet-and-nutrition-booklet WHat do we already know about resistance training and MS?The idea for this post came from a study published at the beginning of August in the Multiple Sclerosis Journal exploring whether resistance exercise can show improvements in MRI and other clinical markers of MS disease progression. The article was quickly picked up and reported by the popular press- albeit with a rather sensationalist and misleading headline - screaming: ‘Resistance training SLOWS the progression of multiple sclerosis and even REVERSES brain shrinkage, study shows for the first time’. Not quite so accurate once you read the full study (reference below) but it got me thinking about how resistance exercise can be beneficial in the management of MS. What do we mean by resistance exercise? Resistance exercise (or strength/weight training) improves the strength of the muscle and its ability to resist force. Whilst this sounds frighteningly 'personal trainer-y' it can be as straightforward as lifting and carrying a bag of shopping (although that's not always as easy as it sounds). Why might resistance training help with my MS? The premise behind study into the role of resistance training to help in MS is based on research indicating that PwMS often show loss of muscle mass over time (muscle atrophy). This muscle atrophy is the result of decreased activity (eg walking and standing etc) and is not restricted to PwMS; muscle atrophy happens to anyone who is not active - or as active as they have been previously - for a period of time. This loss of muscle mass further results in loss of muscular strength making functional tasks such as walking and standing, lifting and carrying even more difficult. In MS there is uncertainty around the origins of atrophy-based impairment; is it as a result of the disease activity per se (ie demyelination and axonal degradation in the central nervous system) and/or the consequence of reduced physical activity levels, in itself driven by effects of the disease? It’s a vicious cycle. A recent systematic review [consensus of results from a number of studies] revealed that despite the suggestion of muscular weakness as a result of disease activity it is evident that MS does not impede the ability of muscles to increase in strength through training, thereby potentially improving ability to complete strength-related functional tasks (eg lifting and carrying). It is worth emphasising that any improvements in strength are task-specific to the individual muscles trained. It is crucial here that you consult a physiotherapist or qualified personal trainer to pinpoint any specific weaknesses so that they can develop a bespoke programme for you; I can't reiterate enough the need to consult a professional on this, exercise can definitely do more harm than good if performed incorrectly. Specific ways in which resistance training can help in MS Since it was established in the last few decades that exercise is beneficial to PwMS (contrary to early advice to avoid exercise altogether for fear of worsening symptoms of fatigue) many studies have attempted to quantify the optimal type and amount of exercise for PwMS. Much of this research has been focussed on resistance training to address the evidence discussed above around muscle atrophy and associated weaknesses; after earlier studies established that aerobic exercise (eg running and cycling) can raise body temperature to levels which may exacerbate symptoms (Uhthoff's phenomenon). More recent studies have shown that resistance exercise may be better tolerated by PwMS due to the shorter bursts of activity/effort required, and frequent rest periods naturally programmed between sets Resistance exercise has been shown to improve:

Some ideas for resistance exercise... Resistance exercise can come from many different sources including:body weight exercises (eg yoga and pilates poses, sit-ups, press ups or squats)

That said, if you enjoy swimming and aren't affected by the temperature of the water, the classes which have foam 'noodles'/ 'water woggles'/ or whatever look great fun and seem to be enjoyed by people of all ages. Maybe take a friend and give it a try! What is the recommended amount of resistance activity? The guidelines for resistance training for PwMS do not seem to differ from that of the population as a whole. My website shows the general population guidelines for physical activity which includes two sessions per week for adults aged 18-65+. As with any activity you should only do what feels achievable and can be completed safely. Your ability is yours alone so only you know what is best for you. Some notes on safety; it is paramount that you keep yourself safe while exercising. Always use a 'spotter' when lifting weights, you never know when you may not be able to complete a planned exercise, so they are there to step in and help. The same advice goes for anyone lifting weights, it is not exclusive to PwMS so always workout with a buddy when using weights; the weights really do hurt if you drop them. See my page on tips for exercising with MS on the website; both from me and the MS trust. And the final words from me... Have a look at my website to understand more about how exercise can help us manage some of our specific MS symptoms. Do let me know if you have enjoyed this post and found it useful. Send me an email (address below); send me a tweet (@healthylifems) or send me a message through the contact page on the website, I'd love to know what you think. Commentary from the MS Society on the study reporting on reversal of brain atrophy Incidentally, the response from Dr David Schley, Research Communications Manager from the MS Society regarding the headline study about resistance training and brain atrophy, reports: 'This small study confirms that exercise can improve muscle strength and mobility in people with MS - results we’ve already seen in other studies. While it didn’t show any significant changes in things like brain volume or the amount of MS lesions, we know that everyone with MS can benefit from being active. MS is unpredictable and exercise can help manage challenging symptoms.' References:

Daily Mail (article) Available at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-4754068/Resistance-training-slows-progression-MS.html#ixzz4r3z33szH Dalgas U., et al (2010) ‘Fatigue, mood and quality of life improves in multiple sclerosis patients after physical resistance training’ Multiple Sclerosis Journal, April 16(4):480-90; doi: 10.1177/1352458509360040. Epub 2010 Mar 1 Filipi, M.L. et al. (2011) ‘Improvement in strength following resistance training in multiple sclerosis patients despite varied disability levels’. Neurorehabilitation, 28(4): 273-82. DOI: 10.3233/NRE-2011-0666 Kjolhede, T., Vissing, K., Dalgas, U. (2012) ‘Multiple sclerosis and progressive resistance training: a systematic review’. Multiple Sclerosis Journal, 0(0) 1-14; doi: 10.1177/1352458512437418 Kjolhede, T., et al (2017) ‘Can resistance training impact MRI outcomes in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis?’ Multiple Sclerosis Journal, August, 1-10; doi: 10.1177/1352458517722645 Mosby’s Medical Dictionary, 19th ed. Elsevier: Missouri Piatta, M.E., et al. (2016) ‘Effect of exercise training in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis’. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2016 Sep; 97(9) 1564-1572. DOI: 10.1016/japmr2016.01.023.Epub 2016. Feb 2016. |

Archives

December 2017

Categories |